Computing History Timeline

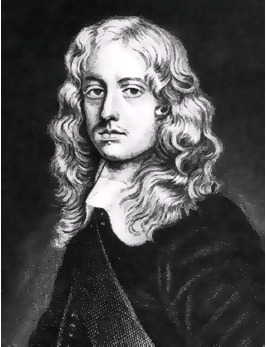

Sir Samuel Morland

Non Decimal Adding Machine

(1625-1695)

Born: 1625

Sulhamstead Bannister, Berkshire

Inventor

Died:

30th December 1695

at Hammersmith, Middlesex

Sir Samuel Moreland, the diplomatist, mathematician and inventor, was born in

1625 at Sulhamstead Bannister

in Berkshire. He was the son of Thomas Moreland, rector of the parish church

there. He entered Winchester School in 1638 and, in May 1644 at the age of

nineteen, entered as a sizar at Magdalene College, Cambridge, where he became

acquainted with Bishop Cumberland. He was elected a fellow of the society, on

30th November 1619, and his name figures as tutor upon the entry of Samuel Pepys

to the college on 1st October 1650. In his manuscript autobiography, preserved

in the library at Lambeth Palace, he states that, after passing nine or ten

years at the university, where he took no degree, he was solicited by some

friends to enter into holy orders but, not deeming himself "fitly qualified", he

devoted his time to mathematical studies, which were the leading pursuit of his

life. His last signature in the college books is dated 1653.

Sir Samuel Moreland, the diplomatist, mathematician and inventor, was born in

1625 at Sulhamstead Bannister

in Berkshire. He was the son of Thomas Moreland, rector of the parish church

there. He entered Winchester School in 1638 and, in May 1644 at the age of

nineteen, entered as a sizar at Magdalene College, Cambridge, where he became

acquainted with Bishop Cumberland. He was elected a fellow of the society, on

30th November 1619, and his name figures as tutor upon the entry of Samuel Pepys

to the college on 1st October 1650. In his manuscript autobiography, preserved

in the library at Lambeth Palace, he states that, after passing nine or ten

years at the university, where he took no degree, he was solicited by some

friends to enter into holy orders but, not deeming himself "fitly qualified", he

devoted his time to mathematical studies, which were the leading pursuit of his

life. His last signature in the college books is dated 1653.

He was a zealous supporter of the Parliamentarian Party and, from 1647 onwards, took part in public affairs. In 1653, he was sent, in Whitolocke's retinue, on an embassy to the Queen of Sweden for the purpose of concluding both an offensive and a defensive alliance. Whitelocke describes him as "a very civil man and an excellent scholar; modest and respectful; perfect in the Latin tongue; an ingenious mechanist'. Morland, according to his own account, was recommended, upon his return in 1654, as an assistant to Secretary Thurloe and, in May 1655, he was sent by Cromwell to the Duke of Savoy to remonstrate with him on cruelties inflicted by him upon the sect of Waldenses or Vaudois, which had strongly excited the English public. Morland carried a message to the Duke beseeching him to rescind his persecuting edicts. He remained, for some time, at Geneva as the English resident and he assisted the Rev. Dr. John Pell, resident ambassador with the Swiss cantons, in distributing the remittances sent by the charitable in England for the relief of the Waldenses. In August 1655, Morland was authorised to announce that the Duke, at the request of the King of France, had granted an amnesty to the Waldenses and confirmed their ancient privileges; and that the natives of the valleys, protestant and catholic, had met, embraced one another with tears and sworn to live in perpetual amity together. During his residence in Geneva, Morland, at Thurloe's suggestion, prepared minutes and procured records, vouchers and attestations from which he might compile a correct history of the Waldenses. He arrived at Whitehall on 18th December 1650 and, shortly afterwards, received the thanks of a select committee, appointed by Cromwell to inquire into his proceedings.

Two years later, Morland published 'The History of the Evangelical Churches of the Valleys of Piemont' (1658). This volume, which was illustrated with sensational prints of the supposed sufferings of the Waldenses, "operated like Fox's Book of Martyrs". Prefixed to the book, is a fine portrait of Morland, engraved by P. Lombart, from a painting by Sir Peter Lely, and an epistle dedicatory to Cromwell, couched in a strain of extreme adulation. In Hellis's 'Memoirs,' it is stated that Morland afterwards withdrew this dedication from all the copies he could lay hands on.

Most of the Waldensian manuscripts brought to England and partly published by Morland were said by him to exhibit the date 1120 and they have been often quoted to prove the fabulous antiquity of the sect, which was falsely alleged to have existed long before the time of Peter Waldensis. Morland's documents have since been proved, however, to be forgeries of moderate skill and ingenuity. Morland was probably misled by incorrect statements of the Waldensian minister, Jean Leger, master of an academy at Geneva, whose 'Histoire Generale des Eglises Evangeliques de Piemont,' published in Amsterdam in 1680, may be regarded as an enlarged edition of Morland's book. Six of the most important manuscript volumes brought over by Morland were long supposed to have mysteriously disappeared from the Cambridge University Library and it was generally believed that they had been abstracted by the puritans. However, they were all discovered by Mr. Henry Bradshaw, in 1862, in their proper places, where they had probably remained undisturbed for centuries.

Morland now became intimately associated with the Government of the Commonwealth and he admits that he was an eye and ear witness of Dr. Hewitt's being "trepanned to death" by Thurloe and his agents. The most remarkable intrigue, however, which came to his knowledge was that usually called Sir Richard Willis's Plot. Its object was to induce King Charles II and his brother to effect a landing on the Sussex Coast, under pretence of meeting many adherents, and to put them both to death the moment they disembarked. This plot is said to have formed the subject of a conference between Cromwell, Thurloe and Willis at Thurloe's office, and the conversation was overheard by Morland, who pretended to be asleep at his desk. Welwood relates that, when Cromwell discovered Morland's presence, he drew his poniard and would have killed him on the spot but for Thurloe's solemn assurance that his secretary had sat up two nights in succession and was certainly fast asleep. From this time, Morland endeavoured to promote the Restoration. In justifying to himself the abandonment of his former principles and associates, he observes that avarice could not be his object, as he was, at this time, living in greater plenty than he ever did after the Restoration, "having a house well furnished, an establishment of servants, a coach, & co, and £1,000 a year to support all this, with several hundred pounds of ready money, and a beautiful young woman to his wife for a companion." In order to save the King's life and promote the Restoration, he eventually went to Breda, where he arrived on 6-16th May 1660, bringing with him letters and notes of importance. The King welcomed him graciously and publicly acknowledged the services he had rendered for some years past.

Grave charges of various kinds were brought against Morland by Sir Richard Willis, when he was pleading for a full pardon in 1661, but they do not seem to have received much credit. Among other statements was one to the effect that Morland boasted that he had "poisoned Cromwell in a posset and that Thurloe had a lick of it, which laid him up for a great while". Pepys originally conceived a low opinion of Morland from the adverse rumours that were circulated about him; but, when he heard his own account of his transactions with Thurloe and Willis, "began to think he was not so much a fool" as he had taken him to be.

The King made him liberal promises of 'future preferment' but these were, for the most part, unfulfilled, in consequence, as Morland supposed, of the enmity of Lord Chancellor Hyde. However, he was, on 18th July 1660, created a baronet, being described as of Sulhamstead Bannister, although it does not appear very clearly whether he was in possession of any considerable property in the parish. He was also made a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber; but this appointment, he says, was rather expensive than profitable, as he was obliged to spend £450 in two days on attending the ceremonies accompanying the coronation. He, indeed, obtained a pension of £500 on the post-office, but his embarrassments obliged him to sell it and, returning to his mathematical studies, he endeavoured, by various experiments and the construction of machines, to earn a livelihood.

by Miriam El Hourani